Dr. Malini’s Cold Tolerance Experiment

By Al Torrens-Martin

On a cold, dark afternoon in December, I was trained in the use of an exciting new scientific instrument: the electrolyte leakage probe. As I learned the method, I felt a little bit like a sorcerer. Even though the steps aren’t very complicated, the result – a flashing number indicating the amount of damage caused to a plant’s cell membrane – felt like it was produced through some kind of magic. This is a little game I like to play when assisting with data processing in the lab. Once I get the hang of a new method – cleaning the probe, inserting it into the test tube, pressing “measure,” and holding the tube still until a number shows up on the screen – I allow my mind to wander. I imagine how past plant physiologists came up with this specific protocol, what kinds of trial and error they went through, and how they could have possibly built such a complex machine to gain these results. It makes me grateful that all I have to do to aid in this process is keep my hand still and press a button.

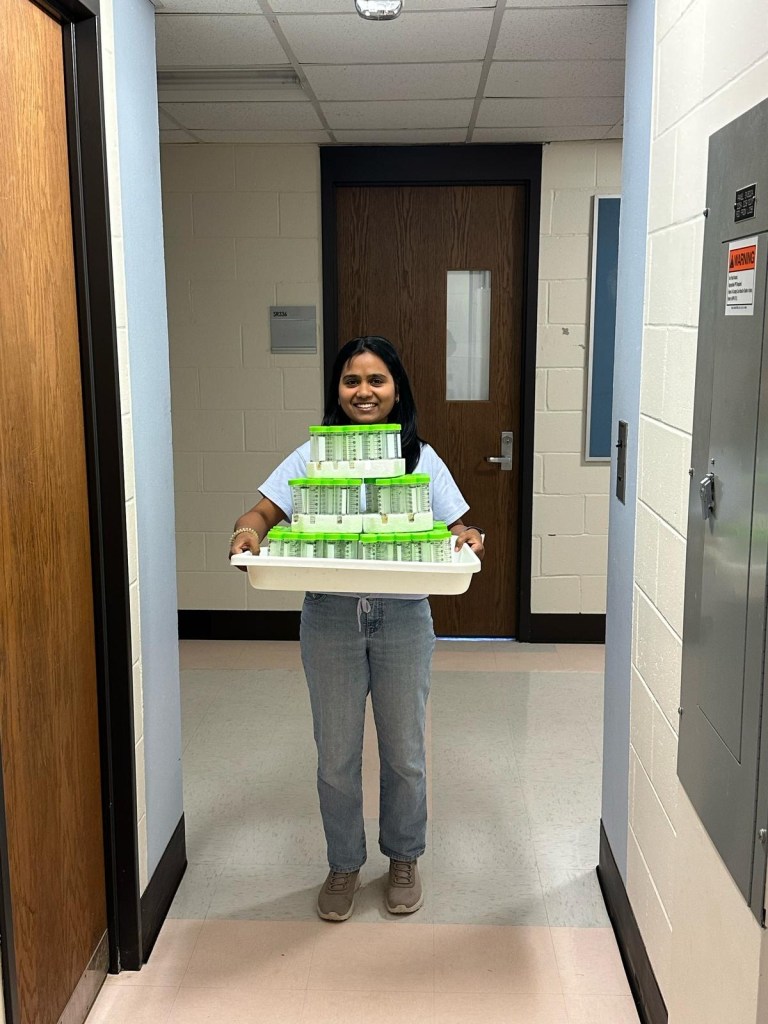

One month later, I am back in the lab, with a behind-the-scenes update on the project behind the electrolyte leakage measurements. Dr. Malini Muthu Karpagam, a postdoc at the PLACE Lab with a PhD in Plant Physiology, has kindly agreed to tell me about her year long research project on the tolerance of native Northeastern Coniferous trees to extreme weather conditions, and what the results could mean for informing future climate change resilience and forestry practices. Malini is from Southern India, and completed her PhD at the Indian Agricultural Research Institute in New Delhi, where she experimented on the heat tolerance of rice crops. Now, in her second year as a postdoc at Smith, she continues her line of questioning on the plant-stress dynamics, but on a much broader, ecophysiological scale.

The goal of Malini’s postdoc project is to gain an understanding of how conifer trees react to environmental changes over a yearlong period. This includes finding out how these trees react to extreme climatic conditions characteristic to New England, such as extreme cold and drought. She is working with 4 different coniferous trees native to the Northeastern US: North Eastern white pine, Eastern hemlock, white cedar and red cedar. She is also curious about how a tree’s age can influence its reaction to cold and drought, so, for each species, Malini samples from both mature trees and seedlings.

To understand how a local conifer responds to “changing environmental conditions over the course of a year,” Malini explains that each tree must be analysed through a range of physiological parameters. As the environment undergoes typical seasonal changes and the extreme events exacerbated by climate change, multiple physiological techniques are needed to capture how trees cope with these stressors. These include traits like photosynthetic rate (also called gas exchange), water potential, osmolyte accumulation and electrolyte leakage. Each of these measurements require specialized, high-tech machines, some of which have been used for decades, and others that, while not quite novel to the field, were completely new to me, like the leakage probe.

For measuring photosynthesis, Malini uses an instrument called IRGA – or Infra-red Gas Analyser. This measures a series of internal and external mechanisms and environmental conditions. Malini explains that “all you have to do is clamp it onto a leaf, wait for 2-3 seconds, and it tells you the photosynthetic rate of the leaf, transpiration rate, stomatal conductance, and internal water conditions.” Quantifying this information, particularly photosynthetic rate, is important for understanding how a tree interacts with changing light intensity – also called photoperiod – and how differences in levels of photosynthesis over the course of a year influence the amount of carbon dioxide a tree can store. The storage of CO2, scientifically referred to as carbon sequestration, is one of the most important ecosystem services trees can provide. The IRGA instrument is also special due to its ability to measure conditions outside of the plant. “It tells you the light intensity at the measurement site; it tells you the humidity, temperature – it has an inbuilt sensor that can sense all of these conditions – the ambient, surrounding conditions,” Malini tells me. “It’s a very handy instrument that every physiological lab should have.”

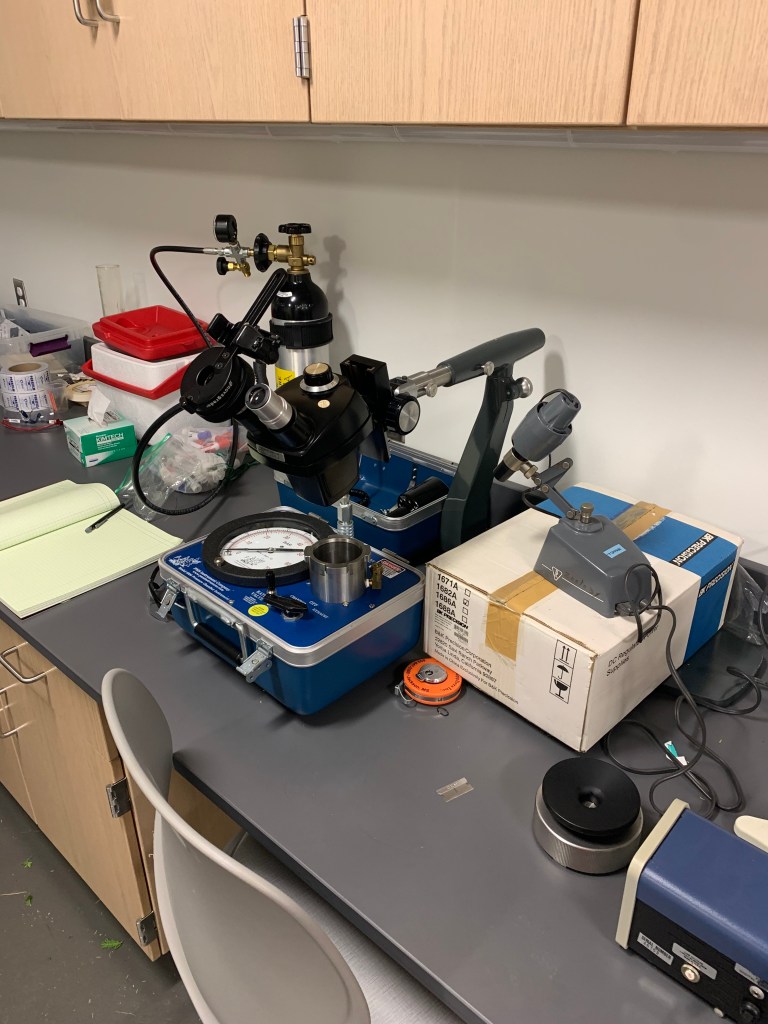

In addition to tracking gas exchange, Malini uses other instruments to find out more about the internal mechanisms of each species, such as cold and drought tolerance, which are both very important for the survival of trees in this region. Measuring drought is tricky, and requires an understanding of a plant’s water potential – or, the amount of energy required to transport water throughout the plant. This can be measured through an instrument called a Scholander pressure bomb. For the pressure bomb, Malini uses twigs – or petioles – from the very end of the branch as samples. The leaf end of the sample is sealed into a plastic bag, then inserted into the chamber, with the petiole sticking out of a small, sealed opening. Pressurized air is then blasted into the machine, until the force of the pressure ejects water out of the petiole. This level of pressure indicates the amount of water potential within the leaf, as it is the amount of potential energy that it takes to move water throughout the sample.

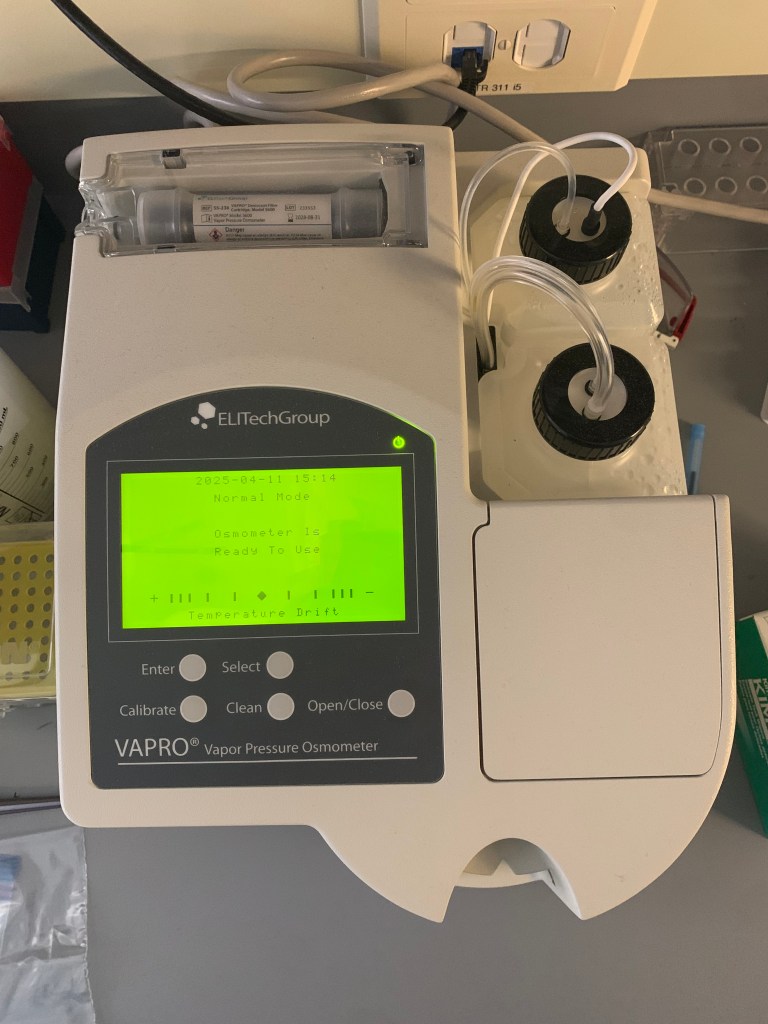

Water potential correlates to the amount of solutes, or “good sugars” in plant cells that can absorb and store water, keeping the plant hydrated. These solutes can be measured by the vapor pressure osmometer, a machine which I have become very familiar with during my time in the lab. Solute potential is closely tied to drought tolerance, because the higher amount of solutes (also called osmolytes) within a plant indicate a higher capacity of this plant to deal with low water availability. In other words, the higher the solute potential, the more drought tolerant the plant is!

Finally, to measure the damage caused to plant cells by cold stress, Malini uses her favorite instrument, the Tenney freezer! She reports that “this is a very new instrument to the field,” its methods requiring a week-long process of cutting leaves into water, exposing them to a range of cold temperatures, placing them on a shaker to release the electrolytes into the water, measuring this liquid with the electrolyte leakage probe, then exposing the samples to a control temperature of -80 degrees to simulate the maximum damage possible, and taking the readings all over again. This is a long and intensive process! But it is worth the wait, as it can reveal important information regarding specific temperatures where plant function is impacted from the cold at the very cellular level.

Many aspects of Malini’s work are complex, and between all the different species, measurements, and instruments used, as well as unreliable environmental conditions that can impact the data, she is quite busy! Because her experiment is so observational, the conditions outside can heavily impact her sampling schedule. For example, when it is cloudy outside, Malini cannot measure for photosynthetic rate, because one of the main aspects of this biological process (the sun) is hidden from view, creating a scenario where numbers could become skewed. Because her job is to measure “the maximum physiological capacity of the plants,” the conditions outside must be sunny, which, as anyone living through winter in New England knows, can be a tall order. Another challenge to this work is the sensitivity of the instruments used. While processing data can sometimes be the perfect time to pretend you are a magical sorcerer, troubleshooting a technical issue with the osmometer, or dealing with the ramifications of rainwater getting inside, can can feel less than magical.

When asked about her favorite part of research, Malini shares that days spent sampling in the field make the whole process worth it. She says that “being in nature – the little hikes you do, the location,” are all part of seeing the larger picture of the research, and connect directly with the trees that are being measured. Malini also really enjoys data analysis, where all the hard work done sampling and measuring is translated into larger trends that either match or challenge the hypothesis. Finding patterns in the data, and seeing connections between all the parameters being measured, “that’s where the study becomes more meaningful,” she says.

Leave a comment