By Al Torrens-Martin

Pictured above are the 2023 summer members of the Smith College PLACE Lab, joined by researchers from the plant biology department at the University of New Hampshire. This image was captured sometime around 5am on a misty morning in August, as we banded together to experience the epic highs and lows of collecting leaf samples for predawn water potential measurements. This intense process was only one step of a larger research project the PLACE lab has been conducting, concerning the water potential and drought resistance of northeastern trees. This sampling in particular was done to collect data on water and pressure potential, and to gain more information about root depth: by quantifying the “dryness” of the leaves, information about root depth is revealed, under the assumption that the deeper the roots are in the ground, the less dry they will be, and the more negative their water potential. Knowing this information about above and below ground plant-water dynamics will further inform the continued investigation on interspecies variation in climate change resilience, as well as offer location based information for foresters and conservationists, ie., which trees should be planted where in order to optimize hydration and long term survival.

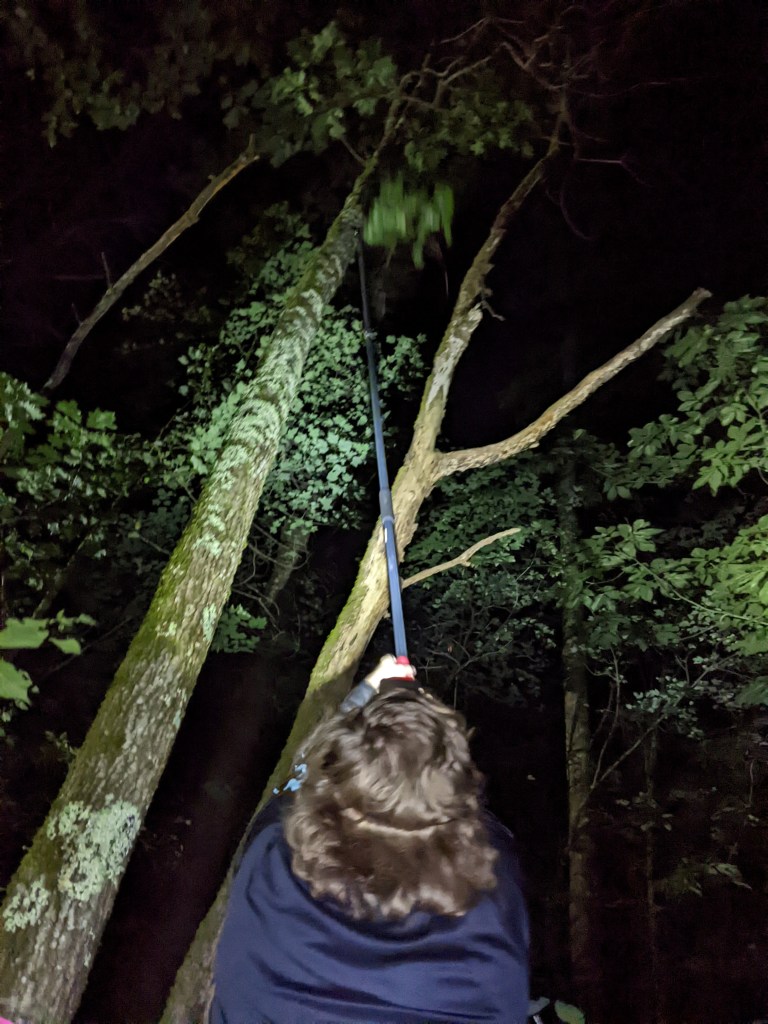

In this preliminary study, leaf samples were chosen depending on several factors, including species, elevation, leaf height and distance from trunk, and the moisture content of surrounding soil. We collected leaves from red maple, red oak, shagbark hickory, American elm American beech, and black birch. We also took age into account, obtaining leaves from both saplings and mature trees to see how this might affect into water conservation strategy. Finally, rather than take our measurements during the usual time (solar noon), we decided collect and process some of our samples prior to the sunrise.

The choice to sample before dawn is not trivial, or because the PLACE Lab is particularly keen on hanging out in the pitch-dark woods: when thinking about leaves as conduits for physiological processes such as photosynthesis and the regulation of water flow, the position of the sun is key. To understand why, an explanation of plant water potential is in order.

Water potential, simply put, is the amount of potential energy that is required to transport water through a plant’s vascular system. It is measured as the sum of solute and pressure potentials, which are, respectively, the amount of solutes (such as carbohydrates and sugars) and the level of pressure within a given cell. This metric can vary based on individual, species, and ecosystem scales. This variation further indicates different levels of preparedness across species to deal with water stress, and hints at future resilience, survival and consequent forest composition.

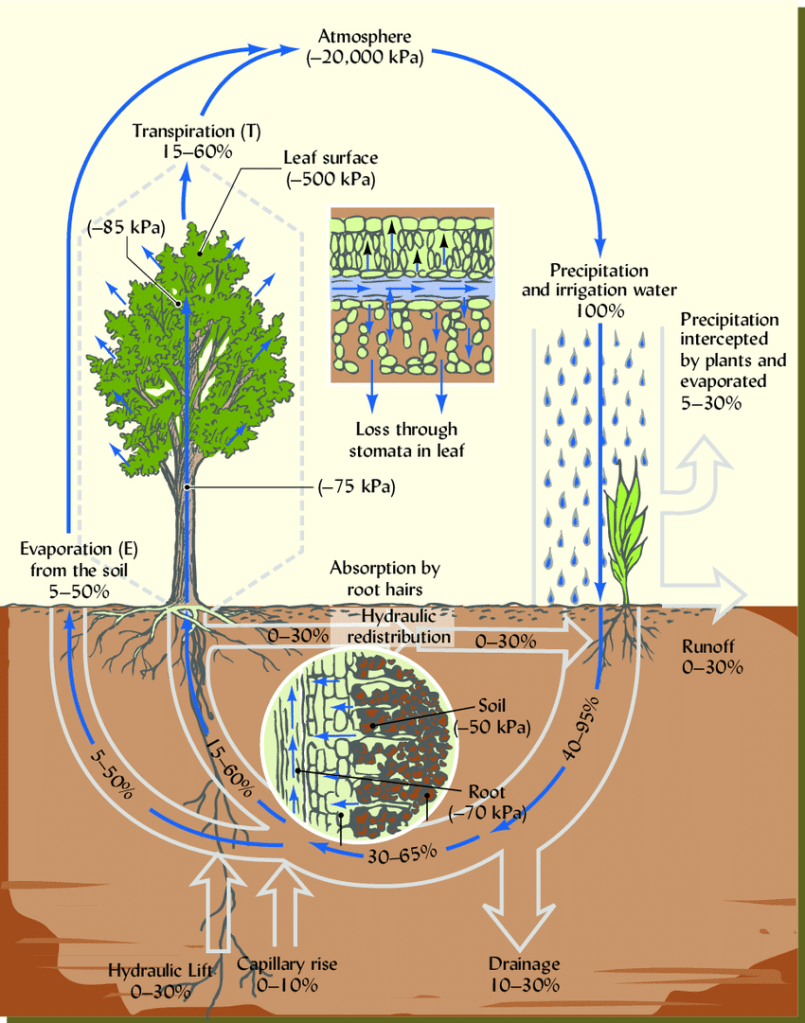

Within individual plants, water is pulled upward through the vascular system through a process known as cohesion-tension theory, which depends both on the process of transpiration, as well as the polarity (and subsequent stickiness) of water molecules. Water first enters the root through osmosis (solutes bind to water molecules, causing the potential energy of those H20s to lower) and because water molecules stick to each other, they are pulled up through the xylem (transport tubes) of the plant, through the pressure provided by the open stomata (the pores on leaf surfaces), where water is transpired from (Ha 2020). The stomata is one of the key controllers of drought management and water conservation strategies; it can regulate its opening and closing mechanisms in response to outside environmental factors, namely solar energy, which oscillates over 24 hour periods. In other words, by being selective about its opening and closing, the stomata can either initiate or limit transpiration rates, and thus has control over water uptake, because of its power to trigger the physiological processes of photosynthesis and transpiration (Vilalta and Garcia-Forner 2017).

Water potential flows along a gradient throughout the plant, starting at the soil where the roots reside, to the atmosphere where water and oxygen are released. This gradient is referred to as the Soil-Plant-Atmosphere-Continuum (SPAC), and moves from high to low, or from “less negative” to “more negative” values (Gersony, personal communication, 2023). Therefore, the higher up the plant the water travels, the more negative its potential becomes.

This gradient works to aid the flow of water through the plant. The surrounding atmosphere is the most negative (which effectively “pulls” water vapor from the stomata during transpiration), and gets less negative the further down the plant it goes, with the soil being the least negative. Normal soil water potential usually lies around 0, and is considered neutral (Gersony, personal communication, 2023). However, due to the influence of the sun on stomatal conductance and transpiration rates, this value changes over 24 hour periods. This is why plant physiologists have theorized that to get the most accurate readings of water potential, it is necessary to obtain and process data right before dawn, as this will have given a plant the entire night away from the sun, and in that time it equilibrates with the neutral soil. By taking pre-dawn samples, scientists obtain a baseline water potential value, which is overall more precise than noon measurements, and can infer drought tolerance from there.

Knowing this gradient makes it easier to visualize the way that water in the soil, as well as atmospheric conditions (such as humidity) are highly influential in the way that plants take up water. Plant physiologists use water potential measurements to asses how much drought stress trees are under at a given time, and how that can vary under different conditions (ie: wet or dry environment, type of tree, time of day/year, to name a few). Knowing which trees are overall more resilient to water stress can help us prepare for rising drought levels, and help keep trees and forests healthy as the effects of climate change continue.

The Place Lab collected leaf samples with this intention, brought them back to the field station, and spend the next several hours measuring initial pressure potential, and hydrating the leaves before putting them into freezers in order to transport them back to Massachusetts. Since then, we have been processing them with an osmometer, and obtaining very interesting data concerning how water potential varies between our variables (species, age, leaf height, and wet vs. dry).

This early morning sampling adventure was personally eye opening for several reasons. When reading scientific papers, or skimming previous water potential research at the beginning of the summer, I’ve developed the unfortunate tendency to skim over the methods sections, and prioritize the results and implications for later research and action. While initially, this was more conducive to my overall understanding of scientific experimentation, it also caused me to take certain aspects of the research and data collection process for granted, such as amount of time, preparation and emotional investment, ie, the heart and soul of fieldwork. The experience of predawn sampling made me appreciate the importance of preparedness, organization before and during sampling, and the trust between lab members and collaborators required for the group to efficiently collect data. Feelings of mutual respect and trust between team members, and the personal investment we each felt to the project itself, made waking up at 3:30 am and traversing into the forest worth the lost hours of sleep. Being one of the people behind the data was heartening, and increased my respect for intense planning that makes fieldwork possible. When looking at methods sections of future papers, I will spend more time reflecting on the complex and emotional story of the data collection, and the network of relationships between crew members, collaborators, and the landscape itself, that make it only possible, but ridiculously fun.

References

Ha, Melissa “4.5.1.1: Water Potential.” 2020. Biology LibreTexts. July 16, 2020. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Botany/Botany_(Ha_Morrow_and_Algiers)/04%3A_Plant_Physiology_and_Regulation/4.05%3A_Transport/4.5.01%3A_Water_Transport/4.5.1.01%3A_Water_Potential.

Martínez-Vilalta, Jordi, and Núria Garcia-Forner. 2017. “Water Potential Regulation, Stomatal Behaviour and Hydraulic Transport under Drought: Deconstructing the Iso/Anisohydric Concept.” Plant, Cell & Environment 40 (6): 962–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/pce.12846.

Brodribb, T., and M. Mencuccini. 2017. “Xylem.” In Encyclopedia of Applied Plant Sciences, 141–48. Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-394807-6.00074-5.

The wise words and advice of Professor Jess Gersony, October 2023.

Images

All photos in this post were taken by Jack Hastings, from University of New Hampshire in July and August, 2023.

SPAC diagram: Brady and Weil. “Soil Water: Characteristics and Behavior.” ResearchGate, Jan 2008. Accessed Nov. 2023. https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Soil-plant-atmosphere-continuum-SPAC-showing-water-movement-from-soil-to-plants-to-the_fig1_233861654

Leave a comment