By Al Torrens-Martin

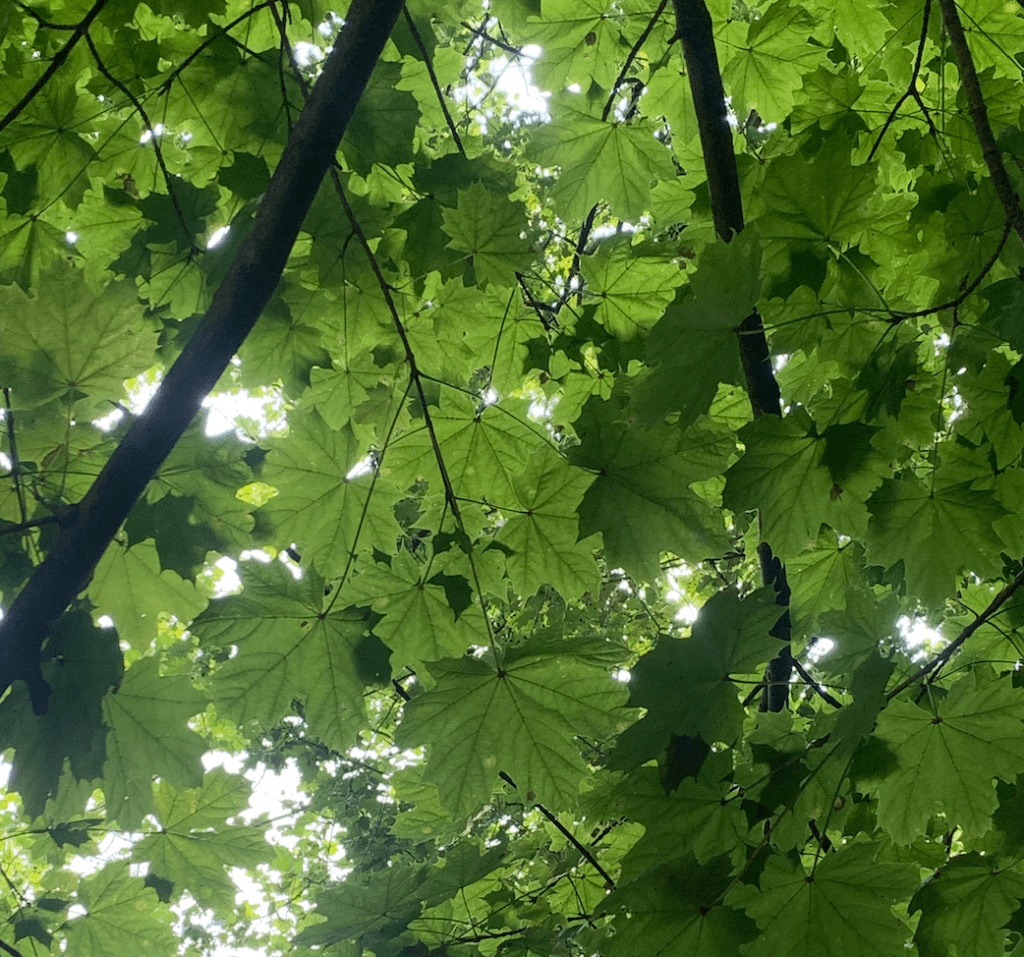

This summer, the PLACE lab at Smith College is involved in many projects, one of which includes sampling data from trees located in the Churchill neighborhood of Holyoke, MA. This is in connection with Holyoke’s Urban Forest Equity Plan, as well as the Urban Trees Ecophysiology Network, which connects several cities in their efforts to study different physiological traits in urban forests, and measure variation within the implementation of urban green space globally. Holyoke’s groundbreaking Urban Forest Equity Plan has been a guidepost for the PLACE Lab, in our efforts to measure dehydration stress in urban trees, and why the maintenance of urban forests is critical to climate change response.

2023)

The integration of greenery into urban spaces has a long history, beginning at the point where human civilization began to take a more concentrated form, and a rift between mankind and the natural world began to develop. This disconnect became even more evident with the rise of the industrial revolution in Europe; this is often cited as the beginning of the anthropocene, which is defined as “the most recent period in Earth’s history when human activity started to have a significant impact on the planet’s climate and ecosystems (national geographic).” Once this rift was established, “nature” in greater Europe was often characterized in the form of estates or parkland that was reserved for only the wealthiest classes and the clergy; the experience of urban greenspace became a sign of prestige (Konijnendijk et al 1997). Soon enough though, outside forests began to be incorporated into nearby cities, and the gap between mankind and the natural world began to close. However, the power dynamic between these two entities had changed, as the concept of nature was carefully developed to fit the conveniences of the elite. Hunting grounds were established for the rich and powerful, and as upper class leisure became more widespread in the late 1800s, more greenspace and “facilities for recreation” were requested to fit this trend (Konijnendijk et al 1997). It was only in the later half of the 20th century that forestry as a professional field began to grow; before this time, land access was an issue between public and state entities; while there was fairly robust involvement from public representatives and policy-makers regarding urban forestry matters, there were not yet careers for those wishing to specialize in conservation or tree health. Over the generations forestry as a field began to develop, and biologists and conservationists alike realized the enormous role of trees in the regulation of climate, as well as their aesthetic value.

American Forests states that “the role of trees is an essential function of city planning and urban infrastructure (American Forests 2019).” Loosely defined, this field relates to the planning, planting, upkeep and maintenance of tree populations in urban settings. This is unquestionably important work, not just for the future of the earth’s climate, but the well being of the residents within these spaces. Healthy, accessible, and equitable greenspace in every city will improve many environmental issues that have been exacerbated by urban infrastructure, such as poor air quality, rising CO2 emissions, water pollution and runoff, and rising temperatures. Trees provide the opportunity to bring the anthropocentric and natural worlds together, and combat the rise of climate change, through their very own physiological mechanisms.

One of the most important ecosystem services provided by trees is their capacity for the removal of harmful atmospheric gasses, the most infamous being carbon dioxide. Through the process of photosynthesis, plants transform CO2 into fresh oxygen, a conversion that is becoming increasingly important as atmospheric carbon rates rise daily. Trees are cited as one of the most efficient means of biological carbon sequestration, which is defined by the US geological survey as “the storage of atmospheric carbon in vegetation, soils, woody products and aquatic environments (USGS).” Because of their size and perennial structure, trees are particularly good at storing large amounts of carbon, through the process of photosynthesis. In forests, carbon sequestration amounts vary depending on time of year, type of tree, moisture availability and other factors (northern woodlands.com). Through processes of cellular respiration, biological decomposition and burning, trees also emit CO2, therefore, proper management in forests, urban and otherwise, is required to ensure that emission rates don’t exceed the trees’ capacity to act as a carbon sink (ibid).

In addition to carbon sequestration, photosynthesis can act as an air filtration mechanism. Poor air quality negatively impacts cardiovascular, respiratory, pulmonary and neurological health, all of which are expected to increase as climate change progresses (urban tree ecophysiology ). However, the very physiology of trees allows them to take in or store volatile gaseous chemicals through either the stomata (a porous hole in the leaf), or the plant surface itself (USDA ). USDA further reports that “pollution removal by urban trees in the United States has been estimated at 711,000 tonnes per year.” However, the health impacts of tree based pollutant removal varies depending on respective population and tree density across the country; the best possible outcomes often come from heavily forested areas with smaller populations. Additionally, this is not always a fail safe procedure, as a buildup of particulate matter on plant surface is reported to sometimes disrupt photosynthetic rate, or are resuspended into the atmosphere through other environmental conditions such as rain or wind.

The process of photosynthesis, and subsequent carbon sequestration and air filtration is incredibly important as a climate resilience measure, especially in cities, which are responsible for the majority of CO2 emissions, and are characterized by their high population density and low tree cover. Therefore, the protection of urban trees is a public health concern; cities will become increasingly unlivable as carbon rates rise and other gaseous air pollutants are released. Additionally, climate change will make urban trees increasingly stressed (Bussotti et al 2014), so the understanding of urban tree ecophysiology and the management of urban trees is a necessary measure for the health of humans and forests in the future.

Another aspect of urban forestry that grows increasingly important is its role in lowering rising temperatures. Many cities experience the urban heat island effect, which occurs when an urbanized area is relatively hotter than its surrounding rural areas, due to more impervious infrastructure, which absorbs and re-emits solar radiation at higher rates than plants or organic materials (EPA 2022). This is exacerbated by the fact that many cities don’t have balanced greenspaces, or lack the appropriate amount or distribution of urban trees. It is predicted to grow worse over time, due to the intense heat waves and severe weather patterns that come with climate change.

Trees have the capacity to relieve some of this heat through the shade they provide. Urban trees can filter or block direct sunlight, and prevent impervious surfaces from overheating, depending on the density of their canopy. Trees also offer direct cooling effects through the process of evapotranspiration, where water vapor is released into the atmosphere through the leaves (Urban Forest Equity Plan). The combination of canopy cover and transpiration effects can cool urban spaces, and reduce high summer temperatures by 2-9 degrees f (EPA ). Well balanced urban forests are essential in order to maximize canopy for shade, while also increasing other positive environmental effects, such as photosynthetic rate.

Finally, urban trees can help to prevent runoff from storm events, and could even play a role in mitigating localized flooding, which has been documented as occurring more commonly in recent years as water levels are rising, and extreme weather events are increasing. Cities, and rural areas with exposed soil (especially farmland), have higher capacity for runoff, as water cannot be absorbed by impervious surfaces and is too intense for dry or unhealthy soil conditions to handle. This allows pollutants to spread, and find their way into nearby water bodies such as rivers and streams. Trees can help to lessen this phenomenon, by soaking up the water before it travels far. This water can be absorbed both through the roots, hydrating the tree, or the canopy, where it undergoes transpiration processes. This can slow flooding events, or minimize intense storms which have the potential to turn into floods, due to the increased risk of flash-flooding in cities (characterized by the fact that water flows faster over impervious surfaces). This not only helps improve the quality of local watersheds, but prevents severe economic damage as well- the cost of planting and maintaining a healthy urban forest is much less than rebuilding homes and businesses after a flooding event (jstor).

The importance of healthy urban greenspace is becoming increasingly clear, and while this has become implemented in many areas, oftentimes it begins and ends with the planting; trees are not properly maintained, and die due to the combination of improper care and the increased stress of their city environment. Bussotti et al write that “urban trees can alleviate some of the effects of climate change on the urban environment, but there is a tradeoff between the beneficial action of urban trees and the detrimental effect that the trees themselves undergo in the urban environment.” The study of stress tolerance in urban trees is becoming increasingly important, in order to understand how to best implement the planting of trees for short and long term climate resilience in urban communities.

Additionally, much like in England several centuries ago, the benefits of urban forestry are often enjoyed only by the wealthy sector; the class divide is evident in many environmental efforts, proving an increasing need for equity within urban forestry efforts. This can be seen in other city planning measures over history, such as redlining across US cities, and the placement of chemical plants in neighborhoods with higher populations of people of color, and larger income disparities. By maintaining a well balanced and equitably distributed urban forest in all cities across the globe, we can begin to tackle issues of class and race, and undo generations of harm, both socially and environmentally.

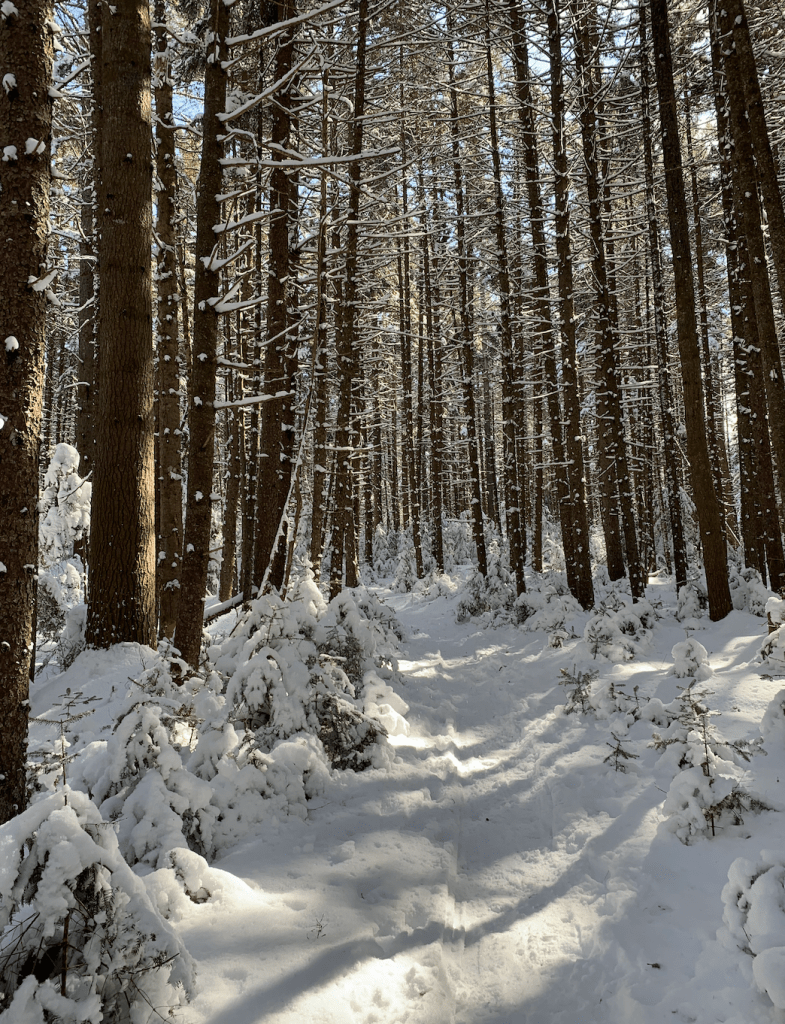

Growing up in Vermont, I was often unaware of climate issues in cities, and viewed their negative environmental impacts as outweighing the community and opportunity that comes from urban living. This summer, I find myself thinking about urban space and cities through a new lens, where greenspace and man-made structures can be combined in a sustainable way, and individuals living in more densely packed communities can enjoy the benefits of trees that I grew up with, and took for granted for much of my life. The deprioritization of urban forestry, and the way it has been manipulated to benefit the wealthy and privileged is one of the issues the PLACE lab has set out to investigate, as well as the fact that the wellbeing of many urban trees is in disarray, and is out of the control of the residents whom the project is supposed to benefit. By sampling urban trees, and collaborating with the Urban Trees Ecophysiology Network, we hope to expand upon the body of urban tree research, and assess the stress tolerance of local northeastern trees in under-forested areas. We also hope to collaborate with the community of Holyoke, and dig into the environmental justice issues that this work so often brushes over.

References! (in order of appearance)

National Geographic Society. “Anthropocene.” Education. Accessed July 31, 2023. https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/anthropocene/.

American Forests. “What is urban forestry: A quick 101.” August 7, 2019. Link

United States Geological Survey. “What’s the difference between geologic and biological carbon sequestration?” Frequently Asked Questions, Energy. Accessed July 31, 2023. Link

Kosiba, Alexandra. “An Introduction to Forest Carbon.” Northern Woodlands, Spring 2023. Link

Bussotti et al. “Ecophysiology of Urban Trees in a Perspective of Climate Change.” AGROCHIMICA, 58(3), July-September 2014. Link

Nowak et al. “Tree and forest effects on air quality and human health in the United States.” Environmental Pollution, 193 (2014) 119-129. Link

United States Environmental Protection Agency. “Learn about heat islands.” September 2, 2022. Accessed July 23, 2023. https://www.epa.gov/heatislands/learn-about-heat-islands

City of Holyoke. “Urban Forest Equity Plan.” Year(?). https://www.holyoke.org/ufep/

Box, Olivia. “Could more Urban Trees Mitigate Runoff and Flooding?” JSTOR Daily, plants and animals. August 22, 2021.

Photo references

Note: All photos save for the one mentioned above were taken by Althea Torrens-Martin.

Leave a comment